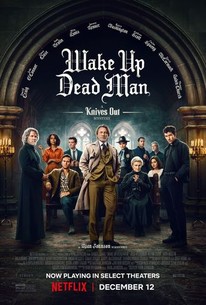

Wake Up Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery

PG-13, 2025, 2h 24m

Genres

Director

Rian Johnson

Writer

Rian Johnson

Stars

Daniel Craig, Josh O’Connor, Glenn Close

Rian Johnson directs a star-studded cast in the third chapter of the Knives Out series. As a grim new case unfolds, Detective Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig) must navigate a deadly web of lies to uncover the truth before the killer strikes again.

Our No Cap Review

Yes or No: Should Christians Watch Wake Up, Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery? (Brief Verdict)

No, this is not recommended for most Christians—especially teens and sensitive viewers—though discerning adults may find redemptive discussion value in its critique of abusive religion and its hunger for real grace.

Wake Up, Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery in a Nutshell

The third Knives Out film drops Benoit Blanc into a decaying upstate New York parish, where a fire-and-brimstone monsignor, a restless young priest, and a disillusioned flock become suspects in an impossible church murder laced with resurrection imagery and ecclesial hypocrisy. The title consciously plays with biblical resurrection language—echoing Christ “waking” Lazarus and Isaiah’s promise that “your dead will live; their bodies will rise” while offering only a twisted, theatrical parody of true Easter hope.

Plot Synopsis

Father Jud Duplenticy, a former boxer turned Catholic priest in upstate New York, is reassigned after punching a rude deacon and sent to assist Monsignor Jefferson Wicks at Our Lady of Perpetual Fortitude, a parish hollowed out by Wicks’ thunderous, shame-driven preaching. Wicks, marked by a bitter family legacy and a vandalized sanctuary whose missing crucifix leaves only a stained outline on the wall, rules a shrinking but fiercely loyal remnant through fear, guilt, and culture-war rhetoric.

During a Good Friday service, Wicks dies suddenly in a storage closet, stabbed in the back with a knife made from a devil-head bar lamp adornment that Jud previously stole and hurled through a church window, making Jud the obvious suspect for police chief Geraldine Scott. Benoit Blanc eventually arrives, “kneeling at the altar of the rational,” and untangles a plot in which town doctor Nat Sharp tranquilizes Wicks, fakes the initial stabbing, later kills him, hides both bodies in a tub of acid, and stages an eerie pseudo-resurrection from the crypt before being exposed in a classic drawing-room-style reveal.

Director & Writers: Background, Beliefs & Worldview

Writer-director Rian Johnson returns to the series with a confessed history of Christian upbringing and distance from active faith, positioning himself as a kind of “former insider” anatomist of religious culture. Earlier Knives Out entries skewered wealth, entitlement, and tech-age vanity; here Johnson shifts his scalpel toward institutional religion—especially authoritarian, shame-based Christianity—while still speaking from a largely secular-progressive moral framework that prizes authenticity, empathy, and systemic critique over confessional theology.

Johnson has described the film as exploring how faith communities can be twisted into vehicles for control and abuse, even while ordinary believers within them sincerely long for healing and justice. That tension—between corrupt shepherds and sincere-but-broken sheep—shapes the film’s world, where the church is simultaneously a site of trauma, a place of longing, and a theater for a very public unmasking.

Any Major Concerns Right off the Bat?

The most immediate concern is the film’s pervasive irreverence: priests are foul-mouthed, a church is visually desecrated, and resurrection iconography is used as a puzzle piece in a murder entertainment rather than as a reverent pointer to Christ’s victory over death. For some viewers, this will not merely be “edgy set dressing” but a genuine stumbling block, as Paul warns against using liberty in ways that wound weaker consciences and cause them to stumble in faith.

Secondly, Johnson’s satire occasionally collapses the distinction between abusive religious leaders and historic Christian doctrine itself, as if fear-based legalism and orthodox faith were the same thing. That conflation risks reinforcing a cultural narrative that equates any claim of divine authority or judgment with manipulation, whereas biblically the good Shepherd lays down his life for the sheep rather than devouring them.

The Core Message: Biblical Resonance or Secular Worldview? (Is it worth a Christian’s time?)

The film’s core message leans toward a secular moral vision—“toxic religion must be exposed, and only love that refuses coercion is trustworthy”—yet it borrows heavily from Christian themes of resurrection, repentance, and shepherding, sometimes in surprisingly sympathetic ways. Father Jud’s insistence that “Christ came to heal the world, not fight it” lands remarkably close to the biblical picture of a Savior who comes not to condemn the world but to save it, even as the movie stops short of grounding that healing in the cross and empty tomb.

At the same time, Blanc explicitly declares himself a “heretic who only kneels at the altar of the practical,” treating Wicks’ corpse as mere meat and faith as narrative, signaling that the ultimate epistemic authority in this universe is human reason, not divine revelation. Christians who watch will therefore need to practice discernment: receiving the movie’s critique of spiritual abuse as a common-grace good, while recognizing that it offers no coherent path to true repentance, reconciliation, or new birth.

Themes & Messages of the Movie

Major themes include:

- Abusive authority vs. Christlike shepherding. Monsignor Wicks embodies a “thunderous and fear-based approach to preaching,” driving people by shame and threat, whereas Jud argues for radical, Christlike love that heals rather than conquers.

- Truth, exposure, and justice. In classic Johnson fashion, the mystery insists that truth will eventually surface, exposing hidden sins—from Wicks’ manipulative ministry to Nat’s murderous pragmatism—echoing the biblical assurance that nothing hidden will not be made known.

- Resurrection as spectacle vs. resurrection as hope. Wicks’ apparent “rising” from the crypt after three days grotesquely riffs on Christ’s resurrection, using the sign of the gospel as a jolting narrative twist rather than a doorway to life.

Theologically, the film rightly identifies that spiritual authority can be weaponized and that a church without a cross (literally, in the stained wall where Wicks refuses to restore the crucifix) has lost the heart of the faith. But it ultimately presents salvation in terms of institutional house-cleaning and personal sincerity, not repentance toward God and faith in Christ’s atoning work.

Iconic Scenes and How Biblical Are They?

1. “Young, dumb, and full of Christ” (Early introduction)

Early on, Jud cheerfully introduces himself as “young, dumb, and full of Christ,” a line delivered with equal parts sincerity and self-mockery that instantly defines him as zealous but immature. On one level, this resembles Paul’s counsel to Timothy not to despise youth but to set an example in speech, love, faith, and purity; on another, the flippant phrasing veers toward the kind of coarse jesting Ephesians warns against, treating the holy name of Christ as the punchline of a personality quip.

2. The vandalized sanctuary and missing crucifix

Flashbacks show Grace, Wicks’ mother, ransacking the church after a betrayed inheritance, smashing statues, tearing apart holy books, and ripping down the crucifix so that only a stained outline remains on the wall. Visually, it is a potent image of apostasy and idolatry: a community that once centered on the crucified Christ now gathers under an empty stain, with Wicks’ power and rage functionally enthroned where the cross ought to be, embodying the biblical warning against shepherds who feed themselves instead of the flock.

3. Good Friday murder and devil-head knife

Wicks’ death on Good Friday, stabbed in the back with a knife fashioned from a devil’s-head lamp ornament, drenches the whodunnit in symbolic irony: the supposed guardian of the altar is literally pierced by an icon of the enemy during the commemoration of Christ’s sacrifice. Rather than participate in Christ’s self-giving love, Wicks dies as a hypocrite whose ministry has been more satanic accusation than gospel invitation, aligning with Christ’s rebukes of religious leaders who “shut the kingdom of heaven in people’s faces.”

4. The fake resurrection from the crypt

The narrative peaks when Wicks apparently rises from his crypt after three days, sending the town into panic before Blanc reveals the trick and the true timeline of Nat’s murders. The timing—not just any return, but after “three days”—is no accident; it deliberately mirrors Christ’s resurrection while emptying it of salvific meaning, reducing what Scripture presents as the firstfruits of new creation to a grotesque jump-scare that, at best, points ironically to the world’s longing for a trustworthy resurrection story.

5. Blanc’s “altar of the practical”

Blanc bluntly calls himself a “heretic who only kneels at the altar of the practical,” and at one point he handles Wicks’ corpse roughly, “like a marinated steak,” insisting it is “just meat, no holy vessel.” This is straightforward philosophical materialism—body as mere matter, death as data point—which stands in sharp contrast to Christian teaching that the body is a temple of the Holy Spirit and that believers await a bodily resurrection unto glory.

Main Characters: Are They Positive or Negative Role Models?

Overall, the movie offers broken people more than aspirational heroes; at its best, it shows how God’s sheep can be wounded by wolves in clerical clothing, reinforcing the need for Christlike, accountable leadership.

Why Was This Movie Made? (Director’s intent)

Johnson has framed this installment as an exploration of faith, community, and loyalty to leaders who may not deserve it, asking how far congregations will let themselves be spiritually and emotionally harmed in the name of “obedience.” Like Knives Out and Glass Onion turned the knife on class and tech celebrity, Wake Up, Dead Man aims to use a crowd-pleasing mystery to provoke questions about religious hypocrisy, institutional rot, and whether the real Jesus would be welcome in many contemporary churches.

In that sense, the film functions as secular prophecy: it names real sins, calls out idolatry of leaders, and suggests that a church without visible cruciform love has betrayed its own story. Yet its solutions remain anthropocentric—expose the villain, redistribute trust, move on—without grappling with the deeper biblical diagnosis of sin and the need for regeneration, not just reform.

Impacts on Culture

Culturally, the film is already sparking conversation among believers and skeptics alike, with Christian reviewers acknowledging both its “content concerns aplenty” and its surprisingly thoughtful take on faith, power, and spiritual abuse. It joins a growing wave of media interrogating church scandals and deconstruction, but stands out for avoiding sexualized exploitation and instead focusing its critique on sermons, structures, and the subtle corruption of the pulpit.

For many non-Christians, Wake Up, Dead Man may function as an interpretive grid for understanding headlines about abusive pastors, offering a richly dramatized “this is what it feels like” portrait of wounded pew-sitters. That makes it both an evangelistic obstacle (if viewers assume all churches look like Wicks’ parish) and a conversation starter for Christians willing to admit institutional sin while pointing beyond Blanc’s rationalism to the crucified and risen Lord the film only shadows.

Content Warnings

Violence & Gore

The movie features multiple violent incidents: Wicks’ stabbing during Good Friday, later revealed as part of a staged and then real murder; the discovery of two corpses dissolving in a tub of acid; and various physical confrontations that echo Jud’s boxing past. While not a gore-fest by horror standards, the imagery of mutilated bodies and acid dissolution is disturbing and viscerally unsettling, raising legitimate concerns for younger viewers and those sensitive to realistic depictions of death.

From a biblical perspective, the problem is not merely that violence is shown but that it is used as dark entertainment, even as Scripture insists that bloodshed cries out to God and that murderers will face judgment. Practically, repeated exposure to stylishly framed killing can dull the conscience and normalize harm as problem-solving, especially for adolescents still forming moral instincts and empathy.

Drug & Alcohol Use

Dr. Nat secretly spikes Wicks’ private flask with tranquilizers, weaponizing the monsignor’s hidden drinking habit as part of the murder scheme. This portrays both substance misuse in leadership and the abuse of pharmaceutical power, underscoring why Scripture commands sobriety and self-control, particularly for those entrusted with care of souls.

Even apart from theology, the scenario highlights real-world dangers: self-medicating clergy under pressure, doctors who rationalize unethical drug use, and the potential for prescription substances to become tools of coercion or harm rather than healing.

Profanity

Multiple reviews note that the priests and parishioners are “foul-mouthed,” with a steady stream of cursing and crude banter played for laughs and character color. This directly conflicts with the biblical call to avoid “filthy language” and “coarse jesting,” not because God is a cosmic language cop, but because speech shapes hearts and communities and reveals underlying reverence or contempt.

Viewers who have grown numb to profanity may not notice, but for families trying to cultivate tongues that bless rather than curse, the constant verbal grime is a real discipleship consideration.

Sexual or Romantic Content

Unlike many “religion exposé” stories, Wake Up, Dead Man deliberately sidesteps sexual violence and explicit romantic entanglements as the focus of its critique. There may be some innuendo and references consistent with the franchise’s PG-13-to-R-style humor, but the central sins here are abuse of power, deception, and violence rather than bodily exploitation.

Biblically, this restraint is welcome—Scripture presents sexuality as covenantal, ordered to marriage, and the misuse of it as both spiritually and physically destructive. Practically, while this film is hardly “pure,” Christians concerned specifically about sexual content may find its focus on verbal and spiritual toxicity a different kind of discernment challenge than the usual on-screen sensuality.

Other Spiritual Concerns

The most serious spiritual issues involve irreverent handling of holy things, from the desecrated sanctuary to the repurposed crucifix space and the parody of resurrection timing. Treating the three-days-in-the-crypt motif as a clever twist flirts with blasphemy—not necessarily in intent, but in effect—because it uses the central miracle of Christian faith as an aesthetic prop rather than as tremble-worthy good news.

Additionally, Blanc’s confident materialism and the film’s occasional conflation of abusive religion with Christianity itself may subtly catechize viewers into believing that any strong doctrine or moral claim is just Wicks in softer clothing. That runs counter to the biblical portrait of Jesus as both gentle and authoritative, full of grace and truth, whose hardest words are reserved not for the broken but for the unrepentantly self-righteous.

Verdict: Why (or Why Not) Should Christians Watch This?

For most believers—especially families, new Christians, and those wounded by church abuse—the cocktail of irreverence, profanity, and violent imagery makes Wake Up, Dead Man more spiritually corrosive than edifying. The film’s genuine insights into spiritual abuse and its occasional near-gospel lines are wrapped in a worldview that ultimately trusts human cleverness and institutional shuffling more than the crucified and risen Christ.

That said, for mature, well-grounded adults who understand its secular presuppositions, the movie can function as a parable of what happens when the church loses the cross, replaces shepherds with warlords, and allows unrepented sin to fester in the pulpit. Such viewers may find it a sharp, painful mirror that prompts confession, reform, and renewed longing for leaders who smell like Jesus, not like smoke and gunpowder.

Recommended Scenes for Discussion

Jud’s “young, dumb, and full of Christ” introduction. Discuss how zeal and immaturity can coexist in ministry, and what it means to grow from raw enthusiasm into sober, steadfast faith without losing joy.

The missing crucifix and stained wall. Explore what happens in real churches when the cross is functionally removed—when sermons become about fear, politics, or self-help rather than Christ crucified.

Good Friday murder with the devil-head knife. Talk about spiritual warfare imagery and how leaders can, in effect, serve the accuser (Satan) when they weaponize guilt rather than proclaim grace.

Wicks’ apparent “resurrection” and its debunking. Contrast this cheap twist with the biblical accounts of resurrection and why the gospel insists that Christ’s rising is not a puzzle but a pledge of new creation.

Blanc’s “altar of the practical.” Use his self-description to discuss the modern temptation to trust only what can be measured, and how Christian faith relates to reason without bowing to it as an idol.

Family Discussion Guide

If a discerning adult chooses to watch (likely without younger kids), these questions can frame a post-viewing conversation:

How might Jesus address each of those people differently—comforting the wounded, confronting the abusive, and inviting the skeptic?

About God and the Church

How does the film’s portrait of Wicks differ from the Good Shepherd of John 10, who lays down his life for the sheep?

Where have you seen real churches drift toward fear-based preaching or personality cults, and what would repentance look like?

About Leaders and Authority

What makes the difference between godly authority and abusive control in the film?

How can congregations hold leaders accountable in biblically faithful, non-vindictive ways?

About Truth and Justice

The movie assumes that truth will eventually “come out”; how does that echo or differ from Scripture’s promise that all hidden things will be revealed in God’s judgment?

Does the film’s resolution feel like justice? Why or why not, and how does that compare to biblical justice that includes mercy and restitution?

About Personal Faith

If you identified most with Jud, Blanc, or a disillusioned parishioner, what does that reveal about your own relationship to faith and the church?

Fun Facts

The fake-resurrection timing (three days in the crypt) is a deliberate nod to Christian resurrection narratives, even if deployed satirically in the mystery structure.

Josh O’Connor, who plays Jud, was reportedly 33 when cast—inviting tongue-in-cheek comparisons to the age of Christ at his crucifixion, a parallel some reviewers have noted.

Blanc gets a goofy “Scooby Dooby Doo” moment, a self-aware wink back to the detective-cartoon roots of the whodunnit genre and his own exaggerated persona.

Similar Movies to Wake Up, Dead Man

For Christians interested in thematically related but varied takes on faith, hypocrisy, and justice:

- Calvary (2014) – A serious, somber drama about a faithful Irish priest facing threats and communal sin, offering a much more explicitly theological meditation on forgiveness and sacrifice.

- Doubt (2008) – A Catholic-school-set drama that probes suspicion, authority, and the weight of allegation in the church, without offering easy answers.

- Spotlight (2015) – Investigates real-world clergy abuse; far harsher and more journalistic, but crucial for understanding institutional sin.

- Knives Out (2019) and Glass Onion (2022) – Earlier Benoit Blanc mysteries that dissect class, entitlement, and tech-era egos with similar wit but less overt theological imagery.

- The Two Popes (2019) – A more sympathetic, dialogue-driven exploration of conscience, institutional change, and differing visions of Catholic leadership.

Each of these comes with its own content concerns, but they collectively provide a richer, more varied cinematic catechism on sin, grace, and the church’s call to reflect Christ rather than Wicks’ warped pulpit.

Explore Latest Book Reviews

-

Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption

Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption 2010, Pages: 528 Genres Writer Laura Hillenbrand Characters Louie Zamperini, Russell Allen Phillips, Pete Zamperini An Olympic runner turned WWII bombardier survives a plane crash, 47 days at sea, and brutal torture as a POW, only to face his hardest battle at home: forgiving…

-

Silence

Silence 1966, Reading Time: 8-10h, Pages: 300 Genres Writer Shūsaku Endō Characters Sebastião Rodrigues, Cristóvão Ferreira, Kichijiro, Tokugawa Inoue Two 17th-century Jesuit priests journey to a Japan hostile to their faith to locate their missing mentor, only to face a test that questions the very nature of God’s presence in suffering. ☕Thus says AI: 89/100…

-

Apocalyptic | Books | Christian Fiction | Christianity | Dystopian | Fantasy | Fiction | Religion | Science Fiction | Suspense/Thriller

Left Behind: A Novel of the Earth’s Last Days

Left Behind: A Novel of the Earth’s Last Days 1995, 5h 21m Genres Authors Jerry B. Jenkins, Larry LaHaye “In the blink of an eye, millions vanished—now, the real nightmare begins for those who stayed.” ☕Our No Cap Review Left Behind in a Nutshell Left Behind is a 1995 novel by evangelical pastor Tim LaHaye and…

-

Books | Christian | Christian Living | Christian Non Fiction | Christianity | Evangelism | Faith | NonFiction | Religion

Gospeler

Gospeler: Turning Darkness into Light One Conversation at a Time Willie Robertson (author) A bold, heartfelt call to share the hope of Jesus through simple conversations that can change a life forever. Genres 224 pages, Paperback First published May 14, 2024 Our No Cap Review Plot Summary Gospeler is Willie Robertson’s personal and practical exploration…

-

Books | Business | Communication | Leadership | Management | NonFiction | Personal Development | Personal Growth | Psychology | Self Help

Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended on It

Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended on It Chris Voss (Author), Tahl Raz (co-author) Never Split the Difference is a bestselling negotiation book written by former FBI lead international hostage negotiator Chris Voss, with journalist Tahl Raz. Drawing from real high-stakes hostage scenarios, corporate negotiations, and cross-cultural conflict resolution, Voss presents…

-

The Hobbit

Middle-earth #0 The Hobbit, or There and Back Again J. R. R. Tolkein The Hobbit is a timeless fantasy adventure that follows Bilbo Baggins, a comfort-loving hobbit from the peaceful Shire, who is unexpectedly swept into a daring quest. When the wizard Gandalf arrives at his doorstep with thirteen determined dwarves led by Thorin Oakenshield,…

Explore Latest Movie Reviews

-

The King of Kings

The King of Kings The King of Kings | © 2025 Angel Studios Category None Light Moderate Heavy Profanity ✓ Violence & Gore ✓ Drug & Alcohol Use ✓ Explicit Content ✓ Spiritual Messaging ✓ 2025, 1h 41m Genres Director Seong-ho Jang Writers Seong-ho Jang, Rob Edwards Stars Oscar Isaac, Kenneth Branagh, Uma Thurman, Pierce…

-

Amazing Grace

Amazing Grace 2006, PG, 2h Genres Director Michael Apted Writers Steven Knight Stars Ioan Gruffudd, Albert Finney, Michael Gambon The idealist William Wilberforce maneuvers his way through Parliament in 19th-century England, endeavoring to end the British transatlantic slave trade. Amazing Grace: When Faith Fuels Revolution A Christian Review of the 2006 Biographical Drama 📊 Rating…

-

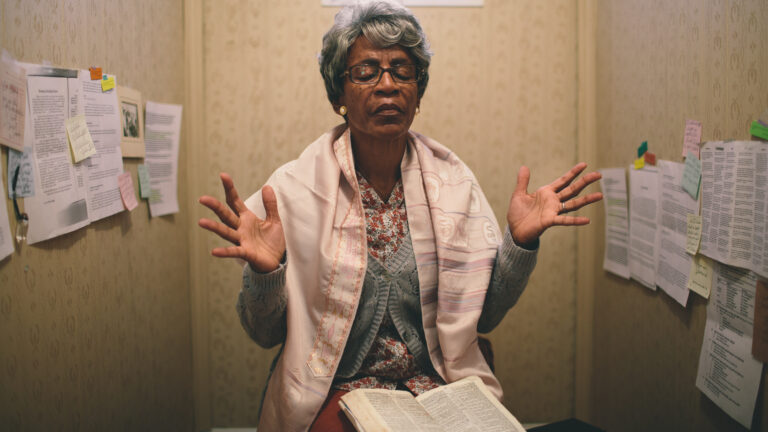

War Room

War Room 2015, PG, 2h Genres Director Alex Kendrick Writers Alex Kendrick, Stephen Kendrick Stars Priscilla C. Shirer, T.C. Stallings, Karen Abercrombie With her marriage on the brink of collapse, a woman discovers that she can only win the battle for her home by surrendering the fight to God in her “war room.” Is War…

-

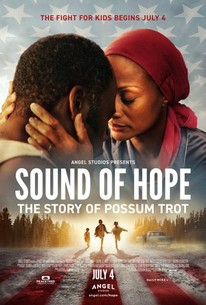

Sound of Hope: The Story of Possum Trot

Sound of Hope: The Story of Possum Trot 2024, PG-13, 2h 10m Genres Director Joshua Weigel Writers Joshua Weigel, Rebekah Weigel Stars Nika King, Demetrius Grosse, Elizabeth Mitchell Inspired by a true story, a rural East Texas pastor and his wife ignite a movement within their small church to adopt 77 of the most difficult-to-place…

-

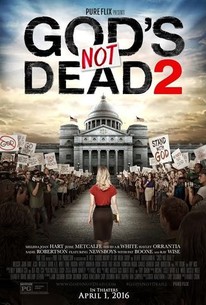

God’s Not Dead 2

God’s Not Dead 2 2016, PG, 2h Genres Director Harold Cronk Writers Chuck Konzelman, Cary Solomon Stars Melissa Joan Hart, Jesse Metcalfe, David A.R. White When a public high school teacher is sued for answering a student’s question about Jesus, she must fight in court to save her career and defend the right to speak…

-

God’s Not Dead

God’s Not Dead 2014, PG, 1h 53m Genres Director Harold Cronk Writers Hunter Dennis, Chuck Konzelman, Cary Solomon Stars Shane Harper, Kevin Sorbo, David A.R. White A devout Christian student must prove God’s existence in a series of debates against his atheist philosophy professor to save his grade and stand up for his faith. ☕Thus…

Explore Latest TV Show Reviews

-

Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption

Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption 2010, Pages: 528 Genres Writer Laura Hillenbrand Characters Louie Zamperini, Russell Allen Phillips, Pete Zamperini An Olympic runner turned WWII bombardier survives a plane crash, 47 days at sea, and brutal torture as a POW, only to face his hardest battle at home: forgiving…

-

Silence

Silence 1966, Reading Time: 8-10h, Pages: 300 Genres Writer Shūsaku Endō Characters Sebastião Rodrigues, Cristóvão Ferreira, Kichijiro, Tokugawa Inoue Two 17th-century Jesuit priests journey to a Japan hostile to their faith to locate their missing mentor, only to face a test that questions the very nature of God’s presence in suffering. ☕Thus says AI: 89/100…

-

Apocalyptic | Books | Christian Fiction | Christianity | Dystopian | Fantasy | Fiction | Religion | Science Fiction | Suspense/Thriller

Left Behind: A Novel of the Earth’s Last Days

Left Behind: A Novel of the Earth’s Last Days 1995, 5h 21m Genres Authors Jerry B. Jenkins, Larry LaHaye “In the blink of an eye, millions vanished—now, the real nightmare begins for those who stayed.” ☕Our No Cap Review Left Behind in a Nutshell Left Behind is a 1995 novel by evangelical pastor Tim LaHaye and…

-

Books | Christian | Christian Living | Christian Non Fiction | Christianity | Evangelism | Faith | NonFiction | Religion

Gospeler

Gospeler: Turning Darkness into Light One Conversation at a Time Willie Robertson (author) A bold, heartfelt call to share the hope of Jesus through simple conversations that can change a life forever. Genres 224 pages, Paperback First published May 14, 2024 Our No Cap Review Plot Summary Gospeler is Willie Robertson’s personal and practical exploration…

-

Books | Business | Communication | Leadership | Management | NonFiction | Personal Development | Personal Growth | Psychology | Self Help

Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended on It

Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended on It Chris Voss (Author), Tahl Raz (co-author) Never Split the Difference is a bestselling negotiation book written by former FBI lead international hostage negotiator Chris Voss, with journalist Tahl Raz. Drawing from real high-stakes hostage scenarios, corporate negotiations, and cross-cultural conflict resolution, Voss presents…

-

The Hobbit

Middle-earth #0 The Hobbit, or There and Back Again J. R. R. Tolkein The Hobbit is a timeless fantasy adventure that follows Bilbo Baggins, a comfort-loving hobbit from the peaceful Shire, who is unexpectedly swept into a daring quest. When the wizard Gandalf arrives at his doorstep with thirteen determined dwarves led by Thorin Oakenshield,…